Rocket Engines

An in-depth look at the propulsion system of rockets.

Reading Time: minute

Audiobook: Not available for this chapter

Disclamer: Most of the illustrations used to explain the different cycles of rocket engines were being designed by Everyday Astronaut (opens in a new tab). All credit for their illustrations goes towards them.

Basic physics of thrust

First of all, we're oversimplifying rockets to a degree that every 3rd grader would understand: A coke bottle with a mentos dropped into it. You read that correctly. Actually, this is pretty much exactly what a pressure-fed rocket is, really.

In the case of our coke bottle, after inserting the piece of Mentos candy into it, there's a lot of pressure created by carbon dioxide bubbles which is why the content of the bottle quickly tries to escape through it's opening - because, loosely explained by the Bernoulli Principle (opens in a new tab), pressure always travel from high to low. Therefore, all we really need is a highly-pressurized propellant tank and a valve on the end of it that's facing the floor and boom - we got ourselves a working rocket.

Right? Yes. But those pressure-fed rockets do have a bottleneck (pun not intended): As previously stated, pressure always flows from high to low, so the propellant tanks would have to be the part of our propulsion system with the highest pressure for propellant to travel out of it. Highly-pressurized tanks would have to have very thick and strong walls to be able to withstand the pressure, meaning they could hold less propellant - assuming same sizes as before.

You could now go ahead and actually build bigger and thicker propellant tanks or you could try to find a way to increase the energy output of your rocket engine. Actually, you might want to do both. But let's take a look at the first one now.

Enthalpy

One way of increasing the energy output of our engine is to increase it's enthalpy. Now, what is enthalpy?

Enthalpy is the sum of the internal energy of our system (or temperature) and the product of it's pressure and volume , therefore: . That means our best bet to increase our energy output would be to increase it's temperature, volume or pressure. One way to achieve this would be by increasing the amount of propellant that can be transported into the combustion chamber, which is basically the exhaust of a rocket, per timeframe. The most "straightforward" way one would come up with might be appending an engine to the pump to power it and make it turn faster. However, an engine for this specific use case would have to be insanely strong. What modern rocket engines instead utilize is a small miniature rocket engine appended to the pump to make it spin extremely fast. This concept is called a preburner!

Let's check out how this would look like to get a better grasp of stuff.

The Open Cycle

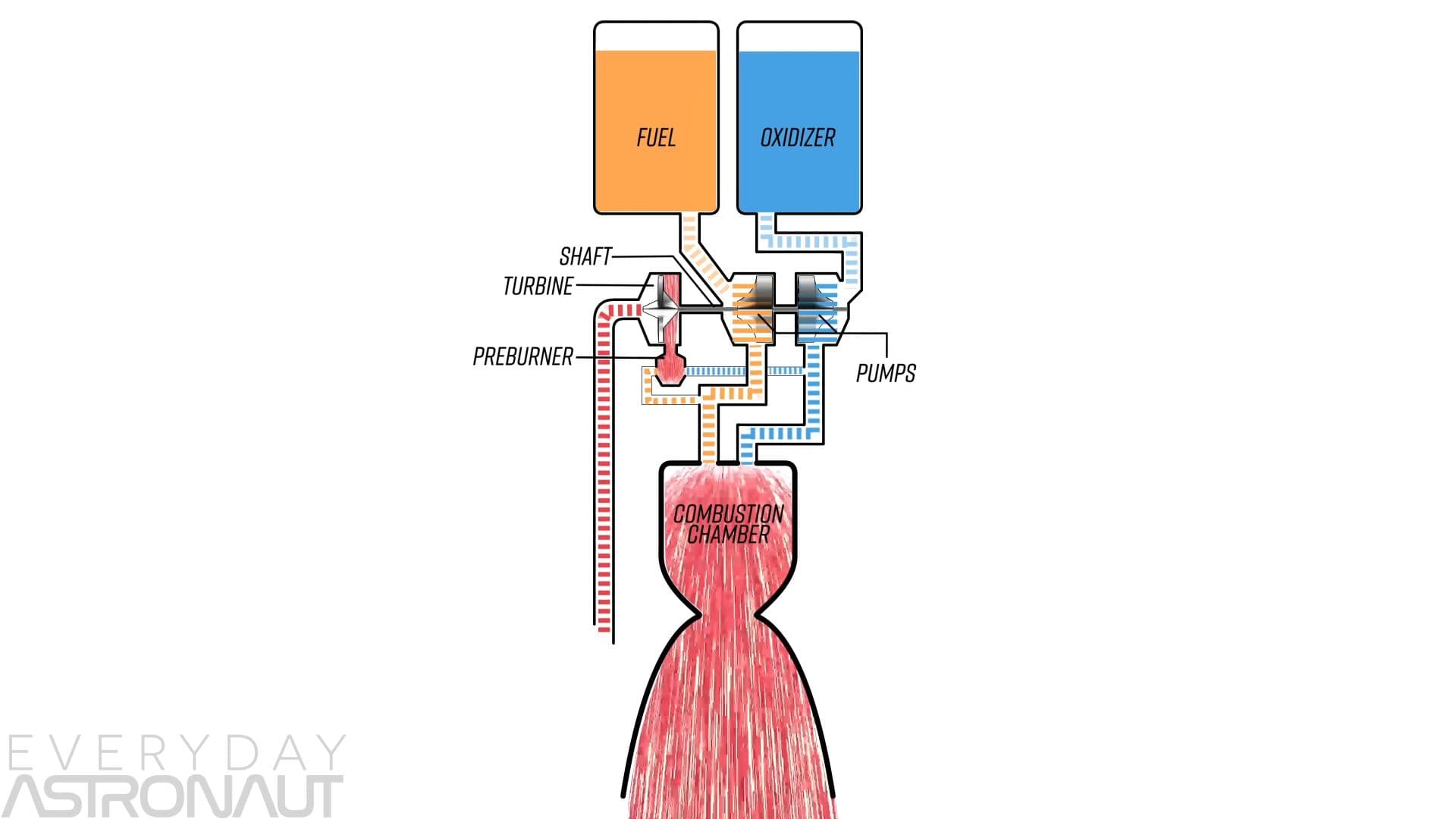

We're going to move through this illustration in a timely chronological manner. First of all, the fuel and oxidizer move from their tanks through pumps. Those pumps move a significant part of the fuel and oxidizer into the combustion chamber where combustion takes place. Combustion is a chemical process in which a substance - in our case called fuel - reacts rapidly with oxygen and gives off heat.

Apart from that, as you can see, a small chunk of both the fuel and oxidizer is transported towards the preburner through smaller pipes. Upon meeting in the preburner, combustion takes place and lots of thrust is created that is faced towards the turbine next to the preburner. The turbine is connected to the pumps via a small shaft that runs through a hole in the middle of both the pumps and the turbine. As soon as the turbine starts spinning really fast due to the thrust coming from the preburner, the pumps are turned faster, meaning they can transport more fuel and oxidizer towards the preburner, creating more thrust, making the turbine and pumps turn even faster - and so on.

Basically, this is the core concept behind all of the rocket systems we're going to look at in here. The only difference between them is their way of dealing with efficiency. As you can see, after being used to power the turbine, excess gas from the preburner is discarded through the pipe on the left. This is why it's called the "Open Cycle". But that can't be very efficient, right?

Running the rocket at an optimal fuel and oxidizer ratio creates an extreme amount of heat that the alloys around it can't support without melting. To keep this from happening, you can run preburners at a less-than-optimal ratio by either using too much fuel (fuel-rich cycle) or too much oxidizer (oxygen-rich cycle). However, you can't close the loop by giving back the hot propellant from the preburner exhaust into the combustion chamber because the soot created from it would clog the injectors and would basically draw your entire engine useless. Worry not though, this isn't the end of the line.

The Closed Cycle

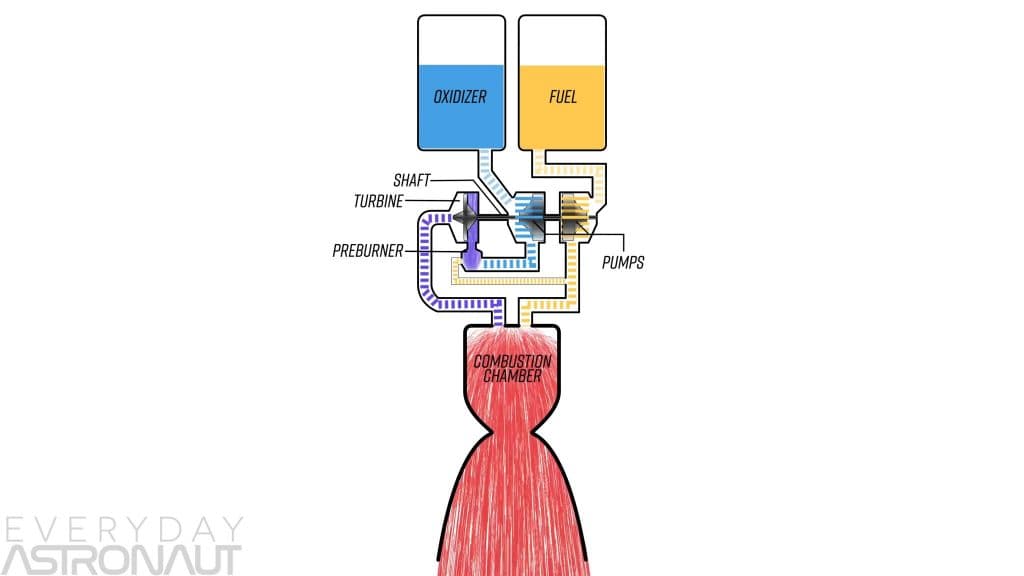

The first solution to the problem mentioned above was brought up by soviet rocket engineers and implemented an oxygen-rich closed cycle.

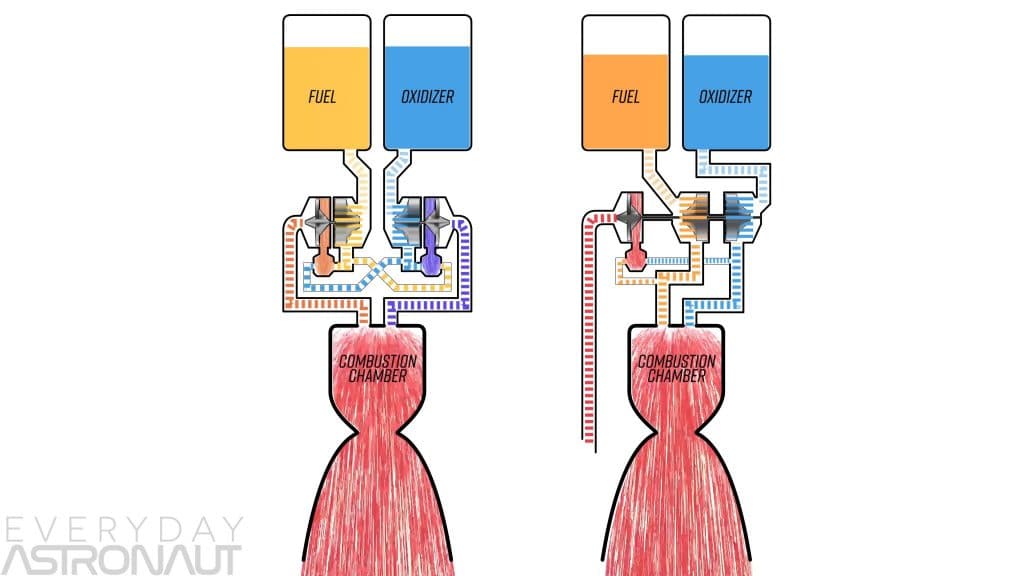

The main difference between the open cycle we looked at before is that in this closed cycle, there isn't just parts of oxidizer going through the preburner and some going directly into the combustion chamber but literally all of the oxidizer going through the preburner where it is then being redirected into the combustion chamber.

So, with this oxygen-rich closed cycle you're giving just enough fuel to the preburner for it to make the turbine and pumps move fast enough so that they can transport as much fuel and oxidizer into the combustion chamber as the optimal ratio allows.

A bit later in time, another attempt at the closed cycle was being made by the US, but they took a bit of a different approach: They used a fuel-rich cycle. But wait, we just learned that the soot from all the propellant would clog the combustion chamber, right? Well, yes, with RP-1, the rocket propellant that was being used in the open cycle of the SpaceX Merlin engine. American engineers dodged that issue by using hydrogen instead of RP-1 as their propellant.

As you can see and probably can decipher by yourself by now, this closed cycle of the RS-25 used not one but two preburners. Both turbopumps get their own preburner, but both of those run fuel-rich and all fuel goes through preburners before it meets the oxidizer in the combustion chamber.

The Full Flow Staged Combustion Cycle

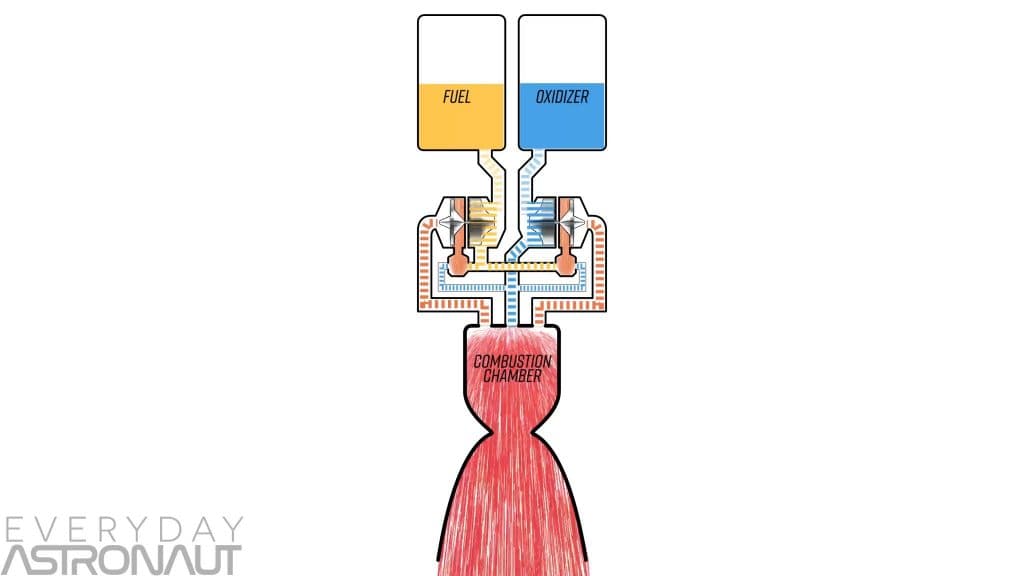

The last kind of cycle we are going to look at is unsurprisingly enough the one that's been praised the "holy grail" or best possible cycle yet but has only been demonstrated to be operable for orbital flight by one single engine to date: SpaceX' Raptor Engine.

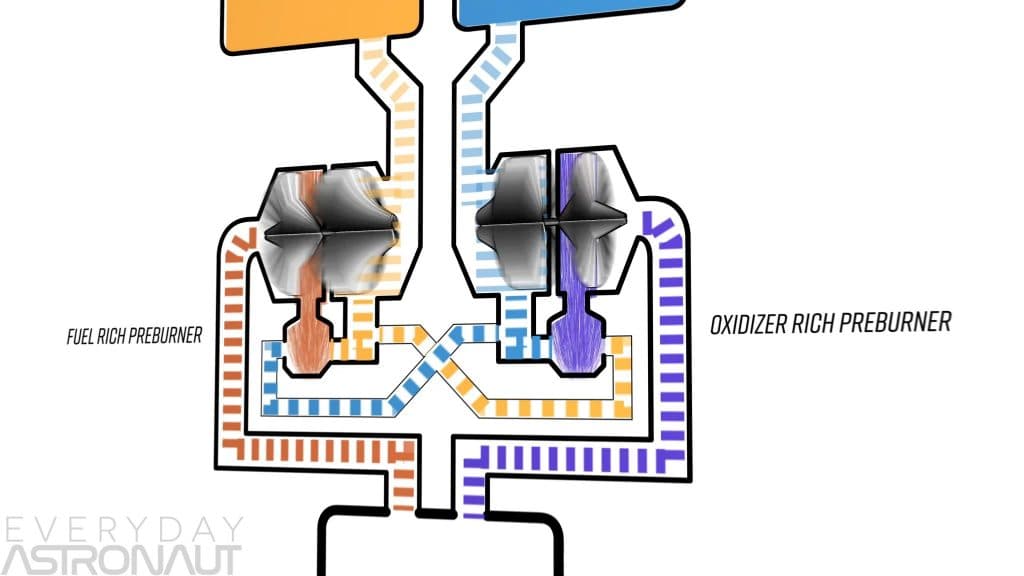

The main engineering difference between previous closed cycles and the full flow cycle is that the closed cycles we've been looking at before have been running either fuel-rich or oxygen-rich, whereas the full flow cycle runs both fuel- and oxygen-rich at the same time.

This works by using two preburners where one is fuel-rich and powers the fuel pump and the other one is oxygen-rich and powers the oxidizer pump. One problem that has previously been solved by the soviets and had to be solved yet again by the Raptor Team at SpaceX was that heated and highly-pressurized oxygen melts basically anything it faces. Similar to the soviets, SpaceX had to develop their own superalloy, namely SX500, to withstand the crazy conditions an oxygen-rich cycle puts the rocket in.

The main benefit of running this specific setup is that both the fuel and oxidizer arrive as a gas in the combustion chamber, making for better combustion and unlocking potentially higher maximum temperatures, which, as we learned earlier, increases enthalpy, which yet again increases the energy output of our system.

When comparing these two, as crazy as the Full Flow cycle is, keep in mind that this isn't some crazy magic solution to the clogging problem we had with the open cycle. Using the same propellant we used in the open cycle, we would clog our combustion chamber exactly like we would in the open cycle before, so this is merely a better solution with another propellant rather than a magic hotfix for the sooting problem.

However, the difference is still remarkable. As you will remember, in an open cycle you only want to use as little fuel and oxidizer in the preburner as possible because all of it is going to be discarded through the preburner exhaust and can't be reused in the combustion process. In the full flow cycle, you literally just throw all the fuel and all the oxidizer into their respective preburners. Additionally, you don't have to worry too much about sealing those because even if some fuel would leak through the seal on the shaft, it would only get in touch with more fuel. If you're scrolling up towards the closed fuel-rich cycle, you'd see why this is an improvement: If fuel from the preburner that powers the oxidizer pump would leak through the seal of the shaft, it would get in touch with the oxidizer and cause a combustion reaction right at the turbopump which obviously is catastrophic.

Conclusion

I personally think it's extremely impressive how the team of engineers at SpaceX solved a rocket cycle that has never been demonstrated to fly to orbit before, simply because you cannot properly anticipate the problems you're going to be facing if you're the first one to do it.

Anyway, this is it for our deep dive into rocket engines. Impressed you sticked through! If you want to learn more about the reasons that made SpaceX come up with methane as fuel for their raptor engines, I highly recommend watching Everyday Astronauts (opens in a new tab) video on this topic. Even apart from that, most of this chapter is inspired from it, I learned most of what I know about engines from them and all of the cycle illustrations I used have been designed by them, either, so they are definitely worth checking out if you just found out you're into rocket science!

Additional Resources

- In this video, Tim Dodd goes into greater detail about the engines we talked about, also showing some more illustrations and videos, potentially making it easier to understand.

- If you prefer learning at your own pace, this article version of the previously mentioned video might be for you.

- Everyday Astronaut uploaded a video together with Elon Musk where Musk explains SpaceX Raptor Engine in great detail, if you still want to learn more about it.